POP already treated extensively about the links between populism, the far right, and nostalgia. In the last year alone, we had a great talk with Francesca Melhuish, who analyzed British nostalgia and Brexit, as well as Ezgi Elçi, who studied Ottoman nostlagia in Turkey.

In this interview, Luca Versteegen shows that nostalgia predicts support for radical right parties and is associated with more negative evaluations of the government.

Enjoy the reading…

1) Let’s start from your decision to study the populist radical right. Is there any personal experience, reading, or piece of research that made you realise that you want to study this phenomenon?

I have two responses to this question. First, the populist radical right is exciting on a scientific level: how can individuals who understand themselves as “ordinary people” support an ideology that is inherently racist, sexist, and exclusionary? What has happened, or does happen, in our societies that motivates people to move towards these radical parties? There are many explanations–including the economy, migration, status threat, and dissatisfaction with mainstream parties. Studying these explanations is interesting, but I think the bigger puzzle is even more fascinating: how can people simultaneously be “ordinary” and “radical”?

The second response is more practical. Radical right parties do not just deserve our academic interests; they challenge our societies. We sometimes forget that. Radical right parties hold, by definition, racist and sexist elements, and they want to exclude certain groups from society. This is highly problematic. I want to understand why so many people support these ideas and how we mitigate support for these ideologies.

2) In a paper recently published, you argue that emotions are a central motivation for radical right voting. Isn’t that true for every type of party? What is special about the link between radical right parties and emotions?

With a background in social psychology, I generally assume that people’s attitudes and behaviours are motivated by their identities and emotions. People are supposed to vote for the party that best represents their policy preferences. However, evidence shows that most people are not that rational. Instead, they often follow their gut or the people they feel connected with. And this historical distinction between rationality and emotionality does not make sense: emotions arise as consequences of stimuli and predict certain information processing and behaviour. This means that emotions are rational because they make you react. If you see a snake, you get anxious. If you’re anxious, you run. This seems like a pretty rational reaction to me.

Emotions are everywhere in politics. They do not just motivate radical right voters. If you are disappointed by a mainstream party, you may turn to another. If you are worried about climate change, you may turn to a Green party. There is much to study on the link between emotions and political behaviour, not only concerning the radical right. That said, radical right politicians seem to be particularly good at using and enticing emotions: they tell people to get angry at the government, be afraid of migrants, or even be disgusted by people with more liberal lifestyles.

3) You argue that nostalgia is particularly important to understand why people vote for populist radical right parties. What type of nostalgia are we talking about? Nostalgia for our youth, for simpler times, for our past life? Or are we talking about nostalgia for a different society, based on different values and ideas?

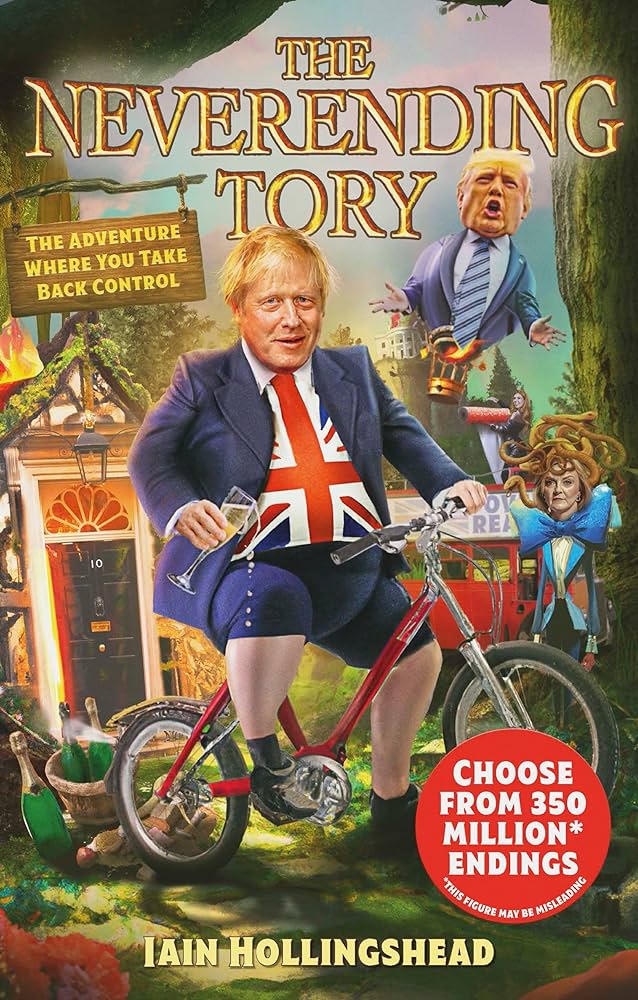

We seem to tacitly assume that populist radical right voters are nostalgic. Nostalgia is defined as a bittersweet longing for the past. We know the common pledges, such as “Make America Great Again” or “Take Back Control.” They suggest that we used to have something–greatness and control–that we no longer have. And it fits another narrative about radical right voters, which says that these people tend to be “left behind.” As I write elsewhere, we have many different understandings of what being “left behind” means, but the emotion that fits best, in my view, is nostalgia.

Lisbon – 2023

Interestingly, however, research from nostalgia experts shows that nostalgia is quite common among many people. Thus, I wanted to know what radical right voters are actually nostalgic about and how this differs from other voters. Using representative panel data from the Netherlands, I find that nostalgia is quite common. However, when you look at different contents of nostalgia, radical right voters tend to be particularly likely to long for “the way society used to be” or “the way people were.” Once you take such content into a model, personal nostalgia contents like your childhood memories, pets, music, and so on are not so relevant for predicting radical right support.

4) Many studies claim that those who vote for the populist radical right experience resentment and anger: how do these feelings relate to nostalgia?

People who feel nostalgic for a specific past in society tend to have a negative view of the present and are more likely to support radical right-wing ideas. However, it is important to note that nostalgia is not the only factor influencing these attitudes. Conservative beliefs and other non-emotional factors also come into play.

It is interesting how nostalgia relates to other emotions. Researchers find that emotions are quite hard to disentangle, and they are often experienced together. For example, I often struggle to say whether I feel bad about something because it makes me angry or anxious. Usually, it’s both. Some excellent papers differentiate these emotions, such as by Rico and colleagues or Vasilopoulos and colleagues. They show that radical right voting primarily results from anger, not anxiety. Resentment seems to mix different emotions, including nostalgia and anger. But if you long for the past and get bitter about the present, why not directly study nostalgia and anger? I think that is the better choice.

5) Looking at the results you obtained in your study, would you say that nostalgia really matter to understand why people vote for populist radical right parties? If yes, in what ways, and why?

Feeling nostalgic makes you dissatisfied with the present. If you idealize the past and think it was better, you might blame the government and vote for parties that promise to fix things or bring back control. My analysis shows that nostalgia for societal content directly predicts support for radical right parties. Additionally, I run mediation analyses and find that nostalgia is associated with more negative evaluations of the government, which then links to radical right voting. We need to be careful with causal interpretations, but given that this is panel data, we can be relatively confident in these links. Overall, feeling nostalgic for the societal past predicts support for radical right parties and sympathy towards these parties and their leaders. Again, I do not say nostalgia is more important than other explanations. But it seems that feeling nostalgic can really drive our political decisions.

6) Your work focuses on the Netherlands: do you think that the results you obtained could travel to other countries as well? Do you think that nostalgia is the same everywhere, and that it always has the same effects?

Research shows that nostalgia is prevalent across cultures. From time to time, most of us long for things we did, places we have seen, or vacations. So, I would say that people are nostalgic almost everywhere, but what people are nostalgic for varies across individuals.

Likewise, when it comes to societal nostalgia, this longing will be about an idealized past of the respective society: in Western European countries, it will often be about times of more economic stability or homogeneous societies. A sizable share of people in post-communist countries long for the communist political system, and in Sweden, it may be more a longing for its exceptional but somewhat foregone welfare state. Thus, future research could benefit from having more cross-national investigations of the link between nostalgia and radical right support (or even other political outcomes) while being considerate of essential differences across societies and their pasts, respectively.

7) Many studies point to the fact that, compared to other party families, populist radical right parties attract younger voters. How do we combine this fact with the discourse about nostalgia we just did? Can young people feel nostalgia for a past they never experienced?

The exciting thing about emotions is that they do not need to make sense from an objective point of view. You can fear flying even though it is very safe from an objective point of view. Thus, people can be nostalgic for things they never experienced; maybe because these things never happened or because they did not experience them themselves.

For example, I interviewed German radical right supporters in 2021, and one young participant was quite nostalgic about the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). Life was better, safer, more harmonic, and funnier those days – that is what she claimed. Besides the fact that it is unlikely that life in this autocratic system felt better than our present, she could not have experienced it herself.

While the GDR collapsed in 1990, she was only born in 2003.

This underlines that populist elite rhetoric drives our emotions. If politicians constantly tell me that society was better in the past, I may get nostalgic for it. And then I vote for politicians who pledge to restore the past.

8) To conclude, a tough question: do you have the impression that we are collectively becoming more and more nostalgic? Do we long for a lost past more than we used to? If yes, why do you think this might be the case?

It is hard to say as I do not know prevalent nostalgia was in the past. The first mention I am aware of is among Swiss soldiers in the 17th century. And given all the rituals and traditions people had in the past, I would be surprised if this were not at least partly due to peoples’ attempts to restore or at least revive the past.

Still, I think current societies give us many reasons to turn away from the present: pandemics, wars, rising inequality, polarization. Observing these developments may stress or unsettle us, and nostalgia may offer us some refuge. It is important to emphasize that nostalgia is not a “negative” emotion: it feels bittersweet because we long for things we like (sweet) and realize that they do not exist anymore (bitter). Moreover, nostalgia has many positive effects on our social relationships, functioning, and well-being. Maybe most importantly, it helps us find meaning. As such, we may even be able to use it in disturbing times.

My paper shows that primarily societal content sparks radical right support. However, future research must examine whether we can also turn nostalgia into more constructive political behaviours.

(Peter) Luca Versteegen is a PhD-candidate at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. In his dissertation, he studies radical right support and affective polarization from a political psychology perspective, where he argues that individuals’ social identities and emotions motivate such political behaviors as reactions to subjectively perceived threatening developments. His broader research agenda aims to identify individual-level factors that motivate constructive, goal-oriented individual behavior and well-being.

He seeks to improve the dissemination of scientific work by engaging in public science communication events. Besides his work, he likes to run, cycle, and explore the world. More information can be found on his university and personal websites.